Chapter 5 War Peace and War Again

Front end folio of War and Peace, showtime edition, 1869 (Russian) | |

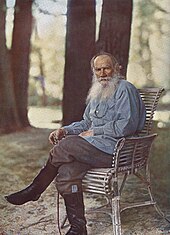

| Author | Leo Tolstoy |

|---|---|

| Original championship | Война и миръ |

| Translator | The offset translation of War and Peace into English language was past American Nathan Haskell Dole, in 1899 |

| Land | Russia |

| Language | Russian, with some French |

| Genre | Novel (Historical novel) |

| Publisher | The Russian Messenger (series) |

| Publication date | Serialised 1865–1867; book 1869 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 1,225 (outset published edition) |

| Followed by | The Decembrists (Abased and Unfinished) |

| Original text | Война и миръ at Russian Wikisource |

| Translation | State of war and Peace at Wikisource |

War and Peace (Russian: Война и мир, romanized: Voyna i mir ; pre-reform Russian: Война и миръ ; [vɐjˈna i ˈmʲir]) is a literary work mixed with chapters on history and philosophy past the Russian author Leo Tolstoy. It was showtime published serially, and so published in its entirety in 1869. It is regarded equally one of Tolstoy'south finest literary achievements and remains an internationally praised classic of globe literature.[1] [2] [3]

The novel chronicles the French invasion of Russia and the impact of the Napoleonic era on Tsarist society through the stories of five Russian aloof families. Portions of an before version, titled The Year 1805,[4] were serialized in The Russian Messenger from 1865 to 1867 before the novel was published in its entirety in 1869.[v]

Tolstoy said that the best Russian literature does not conform to standards and hence hesitated to classify War and Peace, saying it is "not a novel, even less is it a poem, and still less a historical chronicle". Large sections, especially the later capacity, are philosophical discussions rather than narrative.[6] He regarded Anna Karenina equally his offset truthful novel.

Limerick history [edit]

Tolstoy's notes from the ninth draft of War and Peace, 1864.

Tolstoy began writing War and Peace in 1863, the year that he finally married and settled down at his state manor. In September of that year, he wrote to Elizabeth Bers, his sister-in-law, asking if she could notice any chronicles, diaries or records that related to the Napoleonic period in Russia. He was dismayed to find that few written records covered the domestic aspects of Russian life at that time, and tried to rectify these omissions in his early drafts of the novel.[vii] The get-go half of the book was written and named "1805". During the writing of the second half, he read widely and acknowledged Schopenhauer every bit i of his principal inspirations. Tolstoy wrote in a letter of the alphabet to Afanasy Fet that what he had written in State of war and Peace is also said by Schopenhauer in The World equally Will and Representation. Withal, Tolstoy approaches "it from the other side."[eight]

The start draft of the novel was completed in 1863. In 1865, the periodical Russkiy Vestnik (The Russian Messenger) published the showtime part of this draft under the title 1805 and published more the following yr. Tolstoy was dissatisfied with this version, although he allowed several parts of it to be published with a dissimilar catastrophe in 1867. He heavily rewrote the unabridged novel between 1866 and 1869.[5] [nine] Tolstoy's wife, Sophia Tolstaya, copied as many as seven dissever complete manuscripts before Tolstoy considered it ready for publication.[9] The version that was published in Russkiy Vestnik had a very dissimilar ending from the version eventually published under the title State of war and Peace in 1869. Russians who had read the serialized version were eager to buy the consummate novel, and it sold out almost immediately. The novel was immediately translated later publication into many other languages.[ citation needed ]

It is unknown why Tolstoy changed the name to War and Peace. He may have borrowed the title from the 1861 work of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: La Guerre et la Paix ("War and Peace" in French).[iv] The title may besides exist another reference to Titus, described equally being a main of "war and peace" in The Twelve Caesars, written by Suetonius in 119. The completed novel was and so called Voyna i mir ( Война и мир in new-style orthography; in English language War and Peace).[ commendation needed ]

The 1805 manuscript was re-edited and annotated in Russia in 1893 and has been since translated into English language, High german, French, Spanish, Dutch, Swedish, Finnish, Albanian, Korean, and Czech.

Tolstoy was instrumental in bringing a new kind of consciousness to the novel. His narrative structure is noted not only for its god's eye betoken of view over and within events, just too in the way it swiftly and seamlessly portrayed an individual grapheme'southward view bespeak. His use of visual item is ofttimes comparable to movie house, using literary techniques that resemble panning, wide shots and close-ups. These devices, while not sectional to Tolstoy, are part of the new style of the novel that arose in the mid-19th century and of which Tolstoy proved himself a master.[x]

The standard Russian text of War and Peace is divided into four books (comprising fifteen parts) and an epilogue in two parts. Roughly the get-go half is concerned strictly with the fictional characters, whereas the latter parts, besides as the second role of the epilogue, increasingly consist of essays virtually the nature of state of war, power, history, and historiography. Tolstoy interspersed these essays into the story in a style that defies previous fictional convention. Certain abridged versions remove these essays entirely, while others, published even during Tolstoy'south life, just moved these essays into an appendix.[11]

Realism [edit]

The novel is set up 60 years before Tolstoy's day, but he had spoken with people who lived through the 1812 French invasion of Russia. He read all the standard histories bachelor in Russian and French about the Napoleonic Wars and had read letters, journals, autobiographies and biographies of Napoleon and other key players of that era. In that location are approximately 160 real persons named or referred to in War and Peace.[12]

He worked from primary source materials (interviews and other documents), as well as from history books, philosophy texts and other historical novels.[9] Tolstoy besides used a great deal of his own experience in the Crimean War to bring vivid item and first-hand accounts of how the Imperial Russian Army was structured.[13]

Tolstoy was critical of standard history, especially military history, in State of war and Peace. He explains at the start of the novel's third volume his ain views on how history ought to be written.

Language [edit]

Cover of State of war and Peace, Italian translation, 1899.

Although the book is mainly in Russian, meaning portions of dialogue are in French. It has been suggested[xiv] that the apply of French is a deliberate literary device, to portray bamboozlement while Russian emerges as a linguistic communication of sincerity, honesty, and seriousness. It could, withal, as well simply represent some other element of the realistic fashion in which the book is written, since French was the common linguistic communication of the Russian aristocracy, and more generally the aristocracies of continental Europe, at the time.[xv] In fact, the Russian nobility often knew only enough Russian to command their servants; Tolstoy illustrates this by showing that Julie Karagina, a graphic symbol in the novel, is and so unfamiliar with her state's native language that she has to have Russian lessons.

The use of French diminishes as the book progresses. It is suggested that this is to demonstrate Russian federation freeing itself from foreign cultural domination,[14] and to bear witness that a once-friendly nation has turned into an enemy. By midway through the book, several of the Russian aristocracy are eager to find Russian tutors for themselves.

Background and historical context [edit]

The novel spans the period from 1805 to 1820. The era of Catherine the Great was still fresh in the minds of older people. Catherine had made French the language of her purple court.[16] For the next 100 years, it became a social requirement for the Russian dignity to speak French and understand French culture.[16]

The historical context of the novel begins with the execution of Louis Antoine, Duke of Enghien in 1805, while Russian federation is ruled past Alexander I during the Napoleonic Wars. Key historical events woven into the novel include the Ulm Campaign, the Battle of Austerlitz, the Treaties of Tilsit, and the Congress of Erfurt. Tolstoy as well references the Great Comet of 1811 only before the French invasion of Russian federation.[17] : i, vi, 79, 83, 167, 235, 240, 246, 363–364

Tolstoy and so uses the Battle of Ostrovno and the Battle of Shevardino Redoubt in his novel, before the occupation of Moscow and the subsequent fire. The novel continues with the Boxing of Tarutino, the Battle of Maloyaroslavets, the Battle of Vyazma, and the Battle of Krasnoi. The final battle cited is the Battle of Berezina, later which the characters move on with rebuilding Moscow and their lives.[17] : 392–396, 449–481, 523, 586–591, 601, 613, 635, 638, 655, 640

Principal characters [edit]

War and Peace elementary family tree

War and Peace detailed family unit tree

The novel tells the story of five families—the Bezukhovs, the Bolkonskys, the Rostovs, the Kuragins, and the Drubetskoys.

The main characters are:

- The Bezukhovs

- Count Kirill Vladimirovich Bezukhov: the male parent of Pierre

- Count Pyotr Kirillovich ("Pierre") Bezukhov: The primal character and often a vocalisation for Tolstoy's ain beliefs or struggles. Pierre is the socially bad-mannered illegitimate son of Count Kirill Vladimirovich Bezukhov, who has fathered dozens of illegitimate sons. Educated abroad, Pierre returns to Russia equally a misfit. His unexpected inheritance of a big fortune makes him socially desirable.

- The Bolkonskys

- Prince Nikolai Andreich Bolkonsky: The begetter of Andrei and Maria, the eccentric prince possesses a gruff exterior and displays great insensitivity to the emotional needs of his children. Nonetheless, his harshness oft belies subconscious depth of feeling.

- Prince Andrei Nikolayevich Bolkonsky: A stiff simply skeptical, thoughtful and philosophical aide-de-camp in the Napoleonic Wars.

- Princess Maria Nikolayevna Bolkonskaya: Sister of Prince Andrei, Princess Maria is a pious woman whose father attempted to give her a good education. The caring, nurturing nature of her large eyes in her otherwise plain face is frequently mentioned. Tolstoy often notes that Princess Maria cannot claim a radiant beauty (like many other female person characters of the novel) but she is a person of very high moral values and of high intelligence.

- The Rostovs

- Count Ilya Andreyevich Rostov: The pater-familias of the Rostov family; hopeless with finances, generous to a fault. As a result, the Rostovs never accept enough cash, despite having many estates.

- Countess Natalya Rostova: The wife of Count Ilya Rostov, she is frustrated by her married man'south mishandling of their finances, but is determined that her children succeed anyway

- Countess Natalya Ilyinichna "Natasha" Rostova: A central grapheme, introduced every bit "not pretty but full of life", romantic, impulsive and highly strung. She is an accomplished singer and dancer.

- Count Nikolai Ilyich "Nikolenka" Rostov: A hussar, the beloved eldest son of the Rostov family unit.

- Sofia Alexandrovna "Sonya" Rostova: Orphaned cousin of Vera, Nikolai, Natasha, and Petya Rostov and is in love with Nikolai.

- Countess Vera Ilyinichna Rostova: Eldest of the Rostov children, she marries the High german career soldier, Berg.

- Pyotr Ilyich "Petya" Rostov: Youngest of the Rostov children.

- The Kuragins

- Prince Vasily Sergeyevich Kuragin: A ruthless man who is determined to marry his children into wealth at whatsoever cost.

- Princess Elena Vasilyevna "Hélène" Kuragina: A cute and sexually attracting woman who has many affairs, including (it is rumoured) with her brother Anatole.

- Prince Anatole Vasilyevich Kuragin: Hélène'due south blood brother, a handsome and amoral pleasure seeker who is secretly married however tries to elope with Natasha Rostova.

- Prince Ippolit Vasilyevich (Hippolyte) Kuragin: The younger blood brother of Anatole and peradventure near dim-witted of the 3 Kuragin children.

- The Drubetskoys

- Prince Boris Drubetskoy: A poor but aristocratic fellow driven by ambition, fifty-fifty at the expense of his friends and benefactors, who marries Julie Karagina for money and is rumored to accept had an matter with Hélène Bezukhova.

- Princess Anna Mihalovna Drubetskaya: The impoverished female parent of Boris, whom she wishes to push up the career ladder.

- Other prominent characters

- Fyodor Ivanovich Dolokhov: A cold, virtually psychopathic officer, he ruins Nikolai Rostov by luring him into an outrageous gambling debt afterward unsuccessfully proposing to Sonya Rostova. He is also rumored to have had an affair with Hélène Bezukhova and he provides for his poor mother and hunchbacked sis.

- Adolf Karlovich Berg: A young High german officeholder, who desires to be just like everyone else and marries the young Vera Rostova.

- Anna Pavlovna Scherer: Besides known as Annette, she is the hostess of the salon that is the site of much of the novel'south action in Petersburg and schemes with Prince Vasily Kuragin.

- Maria Dmitryevna Akhrosimova: An older Moscow guild lady, skilful-humored but brutally honest.

- Amalia Evgenyevna Bourienne: A Frenchwoman who lives with the Bolkonskys, primarily as Princess Maria's companion and afterward at Maria's expense.

- Vasily Dmitrich Denisov: Nikolai Rostov's friend and blood brother officer, who unsuccessfully proposes to Natasha.

- Platon Karataev: The archetypal skilful Russian peasant, whom Pierre meets in the prisoner-of-war camp.

- Osip Bazdeyev: a Freemason who convinces Pierre to bring together his mysterious group.

- Bilibin: A diplomat with a reputation for cleverness, an acquaintance of Prince Andrei Bolkonsky.

In addition, several real-life historical characters (such as Napoleon and Prince Mikhail Kutuzov) play a prominent function in the book. Many of Tolstoy'southward characters were based on existent people. His grandparents and their friends were the models for many of the master characters; his great-grandparents would have been of the generation of Prince Vassily or Count Ilya Rostov.

Plot summary [edit]

Book Ane [edit]

The novel begins in July 1805 in St. petersburg, at a soirée given by Anna Pavlovna Scherer, the maid of honor and confidante to the dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna. Many of the master characters are introduced equally they enter the salon. Pierre (Pyotr Kirilovich) Bezukhov is the illegitimate son of a wealthy count, who is dying after a series of strokes. Pierre is about to go embroiled in a struggle for his inheritance. Educated away at his begetter's expense following his mother's expiry, Pierre is kindhearted but socially awkward, and finds information technology difficult to integrate into Petersburg society. Information technology is known to everyone at the soirée that Pierre is his father'south favorite of all the quondam count's illegitimate progeny. They respect Pierre during the soiree because his father, Count Bezukhov, is a very rich man, and every bit Pierre is his favorite, almost aristocrats call up that the fortune of his father will exist given to him even though he is illegitimate.

Also attending the soirée is Pierre's friend, Prince Andrei Nikolayevich Bolkonsky, husband of Lise, a charming society favourite. He is disillusioned with Petersburg club and with married life; feeling that his wife is empty and superficial, he comes to hate her and all women, expressing patently misogynistic views to Pierre when the two are solitary. Pierre does not quite know what to do with this, and is made uncomfortable witnessing the marital discord. Pierre had been sent to St Petersburg by his father to choose a career for himself, but he is quite uncomfortable because he cannot observe one and everybody keeps on asking about this. Andrei tells Pierre he has decided to become aide-de-campsite to Prince Mikhail Ilarionovich Kutuzov in the coming state of war (The Battle of Austerlitz) against Napoleon in order to escape a life he cannot stand up.

The plot moves to Moscow, Russian federation's former uppercase, contrasting its provincial, more Russian ways to the more European society of Saint petersburg. The Rostov family is introduced. Count Ilya Andreyevich Rostov and Countess Natalya Rostova are an affectionate couple simply forever worried about their disordered finances. They have iv children. Xiii-year-one-time Natasha (Natalia Ilyinichna) believes herself in love with Boris Drubetskoy, a young human who is nearly to join the army as an officer. The female parent of Boris is Anna Mikhaylovna Drubetskaya who is a childhood friend of the countess Natalya Rostova. Boris is also the godson of Count Bezukhov (Pierre'south begetter). Xx-year-onetime Nikolai Ilyich pledges his love to Sonya (Sofia Alexandrovna), his fifteen-year-old cousin, an orphan who has been brought up past the Rostovs. The eldest child, Vera Ilyinichna, is cold and somewhat haughty but has a good prospective marriage to a Russian-German language officer, Adolf Karlovich Berg. Petya (Pyotr Ilyich) at nine is the youngest; like his blood brother, he is impetuous and eager to join the ground forces when of age.

At Bald Hills, the Bolkonskys' country manor, Prince Andrei departs for war and leaves his terrified, significant wife Lise with his eccentric father Prince Nikolai Andreyevich and devoutly religious sister Maria Nikolayevna Bolkonskaya, who refuses to ally the son of a wealthy aristocrat on account of her devotion to her father and suspicion that the young man would be unfaithful to her.

The second part opens with descriptions of the impending Russian-French state of war preparations. At the Schöngrabern engagement, Nikolai Rostov, at present an ensign in the hussars, has his get-go sense of taste of battle. Boris Drubetskoy introduces him to Prince Andrei, whom Rostov insults in a fit of impetuousness. He is securely attracted by Tsar Alexander's charisma. Nikolai gambles and socializes with his officeholder, Vasily Dmitrich Denisov, and befriends the ruthless Fyodor Ivanovich Dolokhov. Bolkonsky, Rostov and Denisov are involved in the disastrous Boxing of Austerlitz, in which Prince Andrei is badly wounded as he attempts to rescue a Russian standard.

The Battle of Austerlitz is a major event in the book. As the boxing is about to start, Prince Andrei thinks the approaching "twenty-four hours [will] be his Toulon, or his Arcola",[eighteen] references to Napoleon's early victories. After in the boxing, however, Andrei falls into enemy hands and fifty-fifty meets his hero, Napoleon. Just his previous enthusiasm has been shattered; he no longer thinks much of Napoleon, "so petty did his hero with his paltry vanity and delight in victory appear, compared to that lofty, righteous and kindly sky which he had seen and comprehended".[19] Tolstoy portrays Austerlitz as an early on test for Russia, 1 which ended badly because the soldiers fought for irrelevant things like glory or renown rather than the higher virtues which would produce, co-ordinate to Tolstoy, a victory at Borodino during the 1812 invasion.

Book Two [edit]

Volume Two begins with Nikolai Rostov returning on exit to Moscow accompanied past his friend Denisov, his officer from his Pavlograd Regiment. He spends an eventful wintertime at habitation. Natasha has blossomed into a beautiful young woman. Denisov falls in love with her and proposes marriage, but is rejected. Nikolai meets Dolokhov, and they abound closer as friends. Dolokhov falls in love with Sonya, Nikolai's cousin, but as she is in honey with Nikolai, she rejects Dolokhov's proposal. Nikolai meets Dolokhov some time later. The resentful Dolokhov challenges Nikolai at cards, and Nikolai loses every hand until he sinks into a 43,000 ruble debt. Although his mother pleads with Nikolai to ally a wealthy heiress to rescue the family from its dire financial straits, he refuses. Instead, he promises to marry his childhood beat and orphaned cousin, the dowry-less Sonya.

Pierre Bezukhov, upon finally receiving his massive inheritance, is all of a sudden transformed from a bumbling young homo into the most eligible bachelor in Russian guild. Despite knowing that it is incorrect, he is convinced into spousal relationship with Prince Kuragin's beautiful and immoral girl Hélène (Elena Vasilyevna Kuragina). Hélène, who is rumored to be involved in an incestuous matter with her brother Anatole, tells Pierre that she will never have children with him. Hélène is also rumored to exist having an affair with Dolokhov, who mocks Pierre in public. Pierre loses his temper and challenges Dolokhov to a duel. Unexpectedly (considering Dolokhov is a seasoned dueller), Pierre wounds Dolokhov. Hélène denies her affair, only Pierre is convinced of her guilt and leaves her. In his moral and spiritual confusion, Pierre joins the Freemasons. Much of Book Two concerns his struggles with his passions and his spiritual conflicts. He abandons his former carefree beliefs and enters upon a philosophical quest particular to Tolstoy: how should one alive a moral life in an ethically imperfect earth? The question continually baffles Pierre. He attempts to liberate his serfs, only ultimately achieves nothing of annotation.

Pierre is contrasted with Prince Andrei Bolkonsky. Andrei recovers from his near-fatal wound in a military infirmary and returns habitation, only to find his wife Lise dying in childbirth. He is stricken by his guilty conscience for not treating her better. His child, Nikolai, survives.

Burdened with nihilistic disillusionment, Prince Andrei does not return to the army only remains on his estate, working on a project that would formulate military behavior to solve problems of disorganization responsible for the loss of life on the Russian side. Pierre visits him and brings new questions: where is God in this amoral world? Pierre is interested in panentheism and the possibility of an afterlife.

Pierre's wife, Hélène, begs him to have her back, and trying to abide by the Freemason laws of forgiveness, he agrees. Hélène establishes herself as an influential hostess in Petersburg society.

Prince Andrei feels impelled to accept his newly written military notions to Saint Petersburg, naively expecting to influence either the Emperor himself or those close to him. Immature Natasha, also in Saint Petersburg, is caught up in the excitement of her offset thousand ball, where she meets Prince Andrei and briefly reinvigorates him with her vivacious charm. Andrei believes he has found purpose in life again and, after paying the Rostovs several visits, proposes matrimony to Natasha. Even so, Andrei's father dislikes the Rostovs and opposes the marriage, insisting that the couple wait a yr before marrying. Prince Andrei leaves to recuperate from his wounds abroad, leaving Natasha distraught. Count Rostov takes her and Sonya to Moscow in gild to raise funds for her trousseau.

Natasha visits the Moscow opera, where she meets Hélène and her brother Anatole. Anatole has since married a Polish woman whom he abandoned in Poland. He is very attracted to Natasha and determined to seduce her, and conspires with his sister to do and then. Anatole succeeds in making Natasha believe he loves her, somewhen establishing plans to elope. Natasha writes to Princess Maria, Andrei'south sister, breaking off her engagement. At the last moment, Sonya discovers her plans to elope and foils them. Natasha learns from Pierre of Anatole's marriage. Devastated, Natasha makes a suicide attempt and is left seriously sick.

Pierre is initially horrified by Natasha's behavior but realizes he has fallen in love with her. Equally the Great Comet of 1811–12 streaks across the sky, life appears to begin afresh for Pierre. Prince Andrei coldly accepts Natasha's breaking of the engagement. He tells Pierre that his pride will not allow him to renew his proposal.

Volume Three [edit]

The Battle of Borodino, fought on September vii, 1812, and involving more than a quarter of a million troops and seventy thousand casualties was a turning betoken in Napoleon's failed campaign to defeat Russia. It is vividly depicted through the plot and characters of War and Peace.

Painting by Louis-François, Baron Lejeune, 1822.

With the help of her family, and the stirrings of religious faith, Natasha manages to persevere in Moscow through this nighttime flow. Meanwhile, the whole of Russia is afflicted past the coming confrontation between Napoleon's army and the Russian army. Pierre convinces himself through gematria that Napoleon is the Antichrist of the Book of Revelation. Old Prince Bolkonsky dies of a stroke knowing that French marauders are coming for his estate. No organized assistance from any Russian army seems bachelor to the Bolkonskys, just Nikolai Rostov turns upwardly at their estate in time to help put downwards an incipient peasant revolt. He finds himself attracted to the distraught Princess Maria.

Back in Moscow, the patriotic Petya joins a oversupply in audience of Tzar Alexander and manages to snatch a biscuit thrown from the balcony window of the Cathedral of the Assumption by the Tzar. He is near crushed by the throngs in his effort. Nether the influence of the same patriotism, his father finally allows him to enlist.

Napoleon himself is the primary character in this section, and the novel presents him in vivid detail, both personally and as both a thinker and would-exist strategist. Also described are the well-organized force of over four hundred thousand troops of the French Grande Armée (only ane hundred and xl thousand of them actually French-speaking) that marches through the Russian countryside in the tardily summer and reaches the outskirts of the urban center of Smolensk. Pierre decides to leave Moscow and go to watch the Boxing of Borodino from a vantage point next to a Russian arms crew. After watching for a fourth dimension, he begins to join in carrying armament. In the midst of the turmoil he experiences first-mitt the death and devastation of war; Eugène's artillery continues to pound Russian support columns, while Marshals Ney and Davout set a crossfire with artillery positioned on the Semyonovskaya heights. The battle becomes a hideous slaughter for both armies and ends in a standoff. The Russians, however, have won a moral victory by standing upwards to Napoleon's reputedly invincible army. The Russian army withdraws the side by side twenty-four hours, allowing Napoleon to march on to Moscow. Amongst the casualties are Anatole Kuragin and Prince Andrei. Anatole loses a leg, and Andrei suffers a grenade wound in the belly. Both are reported expressionless, but their families are in such disarray that no one can be notified.

Volume Four [edit]

The Rostovs have waited until the last minute to abandon Moscow, fifty-fifty later on it became articulate that Kutuzov had retreated by Moscow. The Muscovites are being given contradictory instructions on how to either abscond or fight. Count Fyodor Rostopchin, the commander in chief of Moscow, is publishing posters, rousing the citizens to put their faith in religious icons, while at the same fourth dimension urging them to fight with pitchforks if necessary. Before fleeing himself, he gives orders to fire the city. However, Tolstoy states that the burning of an abandoned city mostly built of wood was inevitable, and while the French arraign the Russians, these blame the French. The Rostovs accept a difficult time deciding what to have with them, but in the end, Natasha convinces them to load their carts with the wounded and dying from the Boxing of Borodino. Unknown to Natasha, Prince Andrei is amid the wounded.

When Napoleon's regular army finally occupies an abandoned and burning Moscow, Pierre takes off on a quixotic mission to assassinate Napoleon. He becomes anonymous in all the anarchy, shedding his responsibilities past wearing peasant wearing apparel and shunning his duties and lifestyle. The but people he sees are Natasha and some of her family, as they depart Moscow. Natasha recognizes and smiles at him, and he in turn realizes the full telescopic of his beloved for her.

Pierre saves the life of a French officeholder who enters his dwelling looking for shelter, and they have a long, amicable conversation. The next day Pierre goes into the street to resume his assassination plan, and comes across 2 French soldiers robbing an Armenian family. When one of the soldiers tries to rip the necklace off the immature Armenian woman'due south cervix, Pierre intervenes by attacking the soldiers, and is taken prisoner past the French army. He believes he will be executed, but in the end is spared. He witnesses, with horror, the execution of other prisoners.

Pierre becomes friends with a fellow prisoner, Platon Karataev, a Russian peasant with a saintly demeanor. In Karataev, Pierre finally finds what he has been seeking: an honest person of integrity, who is utterly without pretense. Pierre discovers meaning in life simply past interacting with him. Afterward witnessing French soldiers sacking Moscow and shooting Russian civilians arbitrarily, Pierre is forced to march with the 1000 Ground forces during its disastrous retreat from Moscow in the harsh Russian wintertime. Afterwards months of tribulation—during which the fever-plagued Karataev is shot past the French—Pierre is finally freed by a Russian raiding party led by Dolokhov and Denisov, after a minor skirmish with the French that sees the immature Petya Rostov killed in action.

Meanwhile, Andrei has been taken in and cared for by the Rostovs, fleeing from Moscow to Yaroslavl. He is reunited with Natasha and his sister Maria before the finish of the war. In an internal transformation, he loses the fear of death and forgives Natasha in a terminal act before dying.

Nikolai becomes worried about his family's finances, and leaves the regular army after hearing of Petya's decease. There is little promise for recovery. Given the Rostov'due south ruin, he does not feel comfortable with the prospect of marrying the wealthy Marya Bolkonsky, but when they meet again they both still feel honey for each other. As the novel draws to a shut, Pierre's married woman Hélène dies from an overdose of an abortifacient (Tolstoy does not land it explicitly but the euphemism he uses is unambiguous). Pierre is reunited with Natasha, while the victorious Russians rebuild Moscow. Natasha speaks of Prince Andrei'south death and Pierre of Karataev'south. Both are aware of a growing bond between them in their bereavement. With the help of Princess Maria, Pierre finds love at final and marries Natasha.

Epilogue in 2 parts [edit]

First part [edit]

The commencement role of the epilogue begins with the wedding of Pierre and Natasha in 1813. Count Rostov dies soon after, leaving his eldest son Nikolai to take accuse of the debt-ridden estate. Nikolai finds himself with the task of maintaining the family on the verge of bankruptcy. His just treatment of peasants earns him respect and honey, and his situation improves. He and Maria now accept children.

Nikolai and Maria then move to Bald Hills with his mother and Sonya, whom he supports for the rest of their lives. They also raise Prince Andrei's orphaned son, Nikolai Andreyevich (Nikolenka) Bolkonsky.

As in all good marriages, there are misunderstandings, but the couples – Pierre and Natasha, Nikolai and Maria – remain devoted to their spouses. Pierre and Natasha visit Bald Hills in 1820. There is a hint in the closing chapters that the idealistic, adolescent Nikolenka and Pierre would both become part of the Decembrist Uprising. The kickoff epilogue concludes with Nikolenka promising he would do something with which even his late male parent "would be satisfied" (presumably equally a revolutionary in the Decembrist revolt).

Second part [edit]

The second role of the epilogue contains Tolstoy's critique of all existing forms of mainstream history. The 19th-century Great Human being Theory claims that historical events are the result of the actions of "heroes" and other slap-up individuals; Tolstoy argues that this is impossible because of how rarely these deportment result in great historical events. Rather, he argues, great historical events are the result of many smaller events driven by the thousands of individuals involved (he compares this to calculus, and the sum of infinitesimals). He so goes on to fence that these smaller events are the issue of an inverse relationship betwixt necessity and gratis will, necessity being based on reason and therefore explicable through historical analysis, and free will being based on consciousness and therefore inherently unpredictable. Tolstoy also ridicules newly emerging Darwinism as overly simplistic, comparing it to plasterers covering over icons with plaster.

Reception [edit]

The novel that fabricated its author "the truthful king of beasts of the Russian literature" (according to Ivan Goncharov)[20] [21] enjoyed nifty success with the reading public upon its publication and spawned dozens of reviews and analytical essays, some of which (by Dmitry Pisarev, Pavel Annenkov, Dragomirov and Strakhov) formed the basis for the enquiry of later Tolstoy scholars.[21] Nonetheless the Russian press's initial response to the novel was muted, with most critics unable to decide how to allocate it. The liberal paper Golos (The Voice, April iii, #93, 1865) was one of the offset to react. Its anonymous reviewer posed a question later repeated by many others: "What could this possibly be? What kind of genre are we supposed to file it to?.. Where is fiction in it, and where is real history?"[21]

Author and critic Nikolai Akhsharumov, writing in Vsemirny Trud (#six, 1867) suggested that War and Peace was "neither a chronicle, nor a historical novel", but a genre merger, this ambiguity never undermining its immense value. Annenkov, who praised the novel too, was equally vague when trying to allocate information technology. "The cultural history of 1 large section of our society, the political and social panorama of it in the start of the electric current century", was his suggestion. "It is the [social] ballsy, the history novel and the vast picture of the whole nation's life", wrote Ivan Turgenev in his bid to define War and Peace in the foreword for his French translation of "The Two Hussars" (published in Paris by Le Temps in 1875).

In full general, the literary left received the novel coldly. They saw it as devoid of social critique, and keen on the idea of national unity. They saw its major fault equally the "author's disability to portray a new kind of revolutionary intelligentsia in his novel", as critic Varfolomey Zaytsev put it.[22] Articles by D. Minayev, Vasily Bervi-Flerovsky and North. Shelgunov in Delo magazine characterized the novel as "lacking realism", showing its characters as "cruel and rough", "mentally stoned", "morally depraved" and promoting "the philosophy of stagnation". Nonetheless, Mikhail Saltykov-Schedrin, who never expressed his opinion of the novel publicly, in private conversation was reported to have expressed delight with "how strongly this Count has stung our higher lodge".[23] Dmitry Pisarev in his unfinished article "Russian Gentry of Sometime" ( Staroye barstvo , Otechestvennye Zapiski , #2, 1868), while praising Tolstoy'south realism in portraying members of high order, was still unhappy with the way the author, as he saw it, 'idealized' the old nobility, expressing "unconscious and quite natural tenderness towards" the Russian dvoryanstvo. On the opposite front, the conservative press and "patriotic" authors (A. S. Norov and P. A. Vyazemsky among them) were accusing Tolstoy of consciously distorting 1812 history, desecrating the "patriotic feelings of our fathers" and ridiculing dvoryanstvo.[21]

I of the commencement comprehensive articles on the novel was that of Pavel Annenkov, published in #ii, 1868 event of Vestnik Evropy. The critic praised Tolstoy'due south masterful portrayal of man at state of war, marveled at the complexity of the whole composition, organically merging historical facts and fiction. "The dazzling side of the novel", according to Annenkov, was "the natural simplicity with which [the author] transports the worldly diplomacy and big social events down to the level of a character who witnesses them." Annekov thought the historical gallery of the novel was incomplete with the ii "great raznotchintsys", Speransky and Arakcheev, and deplored the fact that the author stopped at introducing to the novel "this relatively crude but original element". In the end the critic called the novel "the whole epoch in the Russian fiction".[21]

Slavophiles declared Tolstoy their " bogatyr " and pronounced War and Peace "the Bible of the new national thought". Several articles on State of war and Peace were published in 1869–70 in Zarya mag past Nikolai Strakhov. "War and Peace is the work of genius, equal to everything that the Russian literature has produced before", he pronounced in the first, smaller essay. "It is now quite articulate that from 1868 when the War and Peace was published the very essence of what we call Russian literature has become quite different, acquired the new form and significant", the critic continued afterwards. Strakhov was the beginning critic in Russia who declared Tolstoy'south novel to exist a masterpiece of a level previously unknown in Russian literature. Yet, being a true Slavophile, he could non fail to come across the novel as promoting the major Slavophiliac ideas of "meek Russian character's supremacy over the rapacious European kind" (using Apollon Grigoriev'due south formula). Years later, in 1878, discussing Strakhov'south own book The World every bit a Whole, Tolstoy criticized both Grigoriev's concept (of "Russian meekness vs. Western animality") and Strakhov'south interpretation of it.[24]

Amid the reviewers were military men and authors specializing in war literature. Most assessed highly the artfulness and realism of Tolstoy's battle scenes. N. Lachinov, a member of the Russky Invalid newspaper staff (#69, April 10, 1868) called the Boxing of Schöngrabern scenes "bearing the highest caste of historical and creative truthfulness" and totally agreed with the writer's view on the Battle of Borodino, which some of his opponents disputed. The ground forces general and respected military author Mikhail Dragomirov, in an commodity published in Oruzheiny Sbornik (The Military Annual, 1868–seventy), while disputing some of Tolstoy's ideas concerning the "spontaneity" of wars and the part of commander in battles, advised all the Russian Army officers to apply War and Peace as their desk book, describing its battle scenes equally "unequalled" and "serving for an ideal manual to every textbook on theories of military art."[21]

Unlike professional literary critics, most prominent Russian writers of the time supported the novel wholeheartedly. Goncharov, Turgenev, Leskov, Dostoyevsky and Fet have all gone on record as declaring State of war and Peace the masterpiece of Russian literature. Ivan Goncharov in a July 17, 1878 alphabetic character to Pyotr Ganzen advised him to choose for translating into Danish War and Peace, adding: "This is positively what might be called a Russian Iliad. Embracing the whole epoch, it is the grandiose literary event, showcasing the gallery of peachy men painted past a lively brush of the peachy principal ... This is one of the most, if non the most profound literary work ever".[25] In 1879, unhappy with Ganzen having chosen Anna Karenina to start with, Goncharov insisted: "War and Peace is the extraordinary verse form of a novel, both in content and execution. It likewise serves equally a monument to Russian history's glorious epoch when whatever figure you lot accept is a colossus, a statue in bronze. Even [the novel's] pocket-size characters carry all the characteristic features of the Russian people and its life."[26] In 1885, expressing satisfaction with the fact that Tolstoy's works had by and so been translated into Danish, Goncharov once more stressed the immense importance of War and Peace. "Count Tolstoy really mounts over everybody else here [in Russian federation]", he remarked.[27]

Fyodor Dostoyevsky (in a May 30, 1871 alphabetic character to Strakhov) described State of war and Peace every bit "the last word of the landlord's literature and the bright 1 at that". In a draft version of The Raw Youth he described Tolstoy as "a historiograph of the dvoryanstvo , or rather, its cultural elite". "The objectivity and realism impart wonderful charm to all scenes, and alongside people of talent, honour and duty he exposes numerous scoundrels, worthless goons and fools", he added.[28] In 1876 Dostoyevsky wrote: "My strong conviction is that a writer of fiction has to accept most profound knowledge—non only of the poetic side of his art, simply also the reality he deals with, in its historical as well equally gimmicky context. Here [in Russia], as far as I see it, only i writer excels in this, Count Lev Tolstoy."[29]

Nikolai Leskov, and then an anonymous reviewer in Birzhevy Vestnik (The Stock Exchange Herald), wrote several manufactures praising highly War and Peace, calling it "the best e'er Russian historical novel" and "the pride of the contemporary literature". Marveling at the realism and factual truthfulness of Tolstoy's book, Leskov idea the writer deserved the special credit for "having lifted up the people'southward spirit upon the high pedestal it deserved". "While working most elaborately upon individual characters, the author, apparently, has been studying most diligently the grapheme of the nation every bit a whole; the life of people whose moral strength came to exist concentrated in the Army that came up to fight mighty Napoleon. In this respect the novel of Count Tolstoy could be seen as an epic of the Great national war which up until at present has had its historians merely never had its singers", Leskov wrote.[21]

Afanasy Fet, in a January one, 1870 alphabetic character to Tolstoy, expressed his slap-up delight with the novel. "You've managed to show us in great detail the other, mundane side of life and explain how organically does it feed the outer, heroic side of it", he added.[xxx]

Ivan Turgenev gradually re-considered his initial skepticism equally to the novel's historical aspect and also the style of Tolstoy's psychological analysis. In his 1880 commodity written in the class of a letter addressed to Edmond Abou, the editor of the French newspaper Le XIXe Siècle , Turgenev described Tolstoy equally "the about popular Russian writer" and War and Peace as "1 of the most remarkable books of our age".[31] "This vast work has the spirit of an epic, where the life of Russia of the get-go of our century in full general and in details has been recreated by the hand of a true principal ... The mode in which Count Tolstoy conducts his treatise is innovative and original. This is the not bad work of a great writer, and in it in that location's true, real Russian federation", Turgenev wrote.[32] Information technology was largely due to Turgenev's efforts that the novel started to gain popularity with the European readership. The starting time French edition of the War and Peace (1879) paved the way for the worldwide success of Leo Tolstoy and his works.[21]

Since then many world-famous authors take praised War and Peace every bit a masterpiece of world literature. Gustave Flaubert expressed his delight in a January 1880 letter to Turgenev, writing: "This is the starting time grade work! What an creative person and what a psychologist! The first ii volumes are exquisite. I used to utter shrieks of please while reading. This is powerful, very powerful indeed."[33] Afterward John Galsworthy called State of war and Peace "the all-time novel that had ever been written". Romain Rolland, remembering his reading the novel as a student, wrote: "this work, like life itself, has no beginning, no end. It is life itself in its eternal move."[34] Thomas Isle of man thought War and Peace to exist "the greatest always war novel in the history of literature."[35] Ernest Hemingway confessed that it was from Tolstoy that he had been taking lessons on how to "write about war in the most straightforward, honest, objective and stark way." "I don't know anybody who could write most war better than Tolstoy did", Hemingway asserted in his 1955 Men at War. The All-time War Stories of All Fourth dimension album.[21]

Isaak Babel said, after reading State of war and Peace, "If the world could write past itself, it would write like Tolstoy."[36] Tolstoy "gives us a unique combination of the 'naive objectivity' of the oral narrator with the interest in particular feature of realism. This is the reason for our trust in his presentation."[37]

English language translations [edit]

War and Peace has been translated into many languages. It has been translated into English on several occasions, starting with Clara Bong working from a French translation. The translators Constance Garnett and Louise and Aylmer Maude knew Tolstoy personally. Translations take to deal with Tolstoy's often peculiar syntax and his fondness for repetitions. Only about 2 percent of State of war and Peace is in French; Tolstoy removed the French in a revised 1873 edition, only to restore it later.[xiv] Virtually translators follow Garnett retaining some French; Briggs and Shubin use no French, while Pevear-Volokhonsky and Amy Mandelker's revision of the Maude translation both retain the French fully.[14]

List of English translations [edit]

(Translators listed.)

Full translations:

- Clara Bell (New York: Gottsberger, 1886). Translated from a French version

- Nathan Haskell Dole (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., 1889)

- Leo Wiener (Boston: Dana Estes & Co., 1904)

- Constance Garnett (London: Heinemann, 1904)

- Aylmer and Louise Maude (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1922–23)

- Revised by Amy Mandelker (Oxford Academy Press, 2010)

- Rosemary Edmonds (Penguin, 1957; revised 1978)

- Ann Dunnigan (New American Library, 1968)

- Anthony Briggs (Penguin, 2005)

- Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Random House, 2007)

- Daniel H. Shubin (self-published, 2020)

Abridged translation:

- Princess Alexandra Kropotkin (Doubleday, 1949)[17]

Translation of draft of 1863:

- Andrew Bromfield (HarperCollins, 2007). Approx. 400 pages shorter than English translations of the finished novel

Comparing translations [edit]

In the Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English language, bookish Zoja Pavlovskis-Petit has this to say nearly the translations of War and Peace available in 2000: "Of all the translations of War and Peace, Dunnigan'due south (1968) is the best. ... Different the other translators, Dunnigan even succeeds with many characteristically Russian folk expressions and proverbs. ... She is true-blue to the text and does not hesitate to render conscientiously those details that the uninitiated may observe bewildering: for example, the argument that Boris'due south mother pronounced his name with a stress on the o – an indication to the Russian reader of the former lady'southward affectation."

On the Garnett translation Pavlovskis-Petit writes: "her ...War and Peace is frequently inexact and contains too many anglicisms. Her style is awkward and turgid, very unsuitable for Tolstoi." On the Maudes' translation she comments: "this should take been the best translation, only the Maudes' lack of adroitness in dealing with Russian folk idiom, and their style in general, place this version below Dunnigan's." She further comments on Edmonds'south revised translation, formerly on Penguin: "[it] is the work of a sound scholar just not the all-time possible translator; information technology ofttimes lacks resourcefulness and imagination in its use of English. ... a respectable translation but non on the level of Dunnigan or Maude."[38]

Adaptations [edit]

Motion-picture show [edit]

- The first Russian adaptation was Война и мир ( Voyna i mir ) in 1915, which was directed past Vladimir Gardin and starred Gardin and the Russian ballerina Vera Karalli. Fumio Kamei produced a version in Japan in 1947.

- The 208-minute-long American 1956 version was directed by King Vidor and starred Audrey Hepburn (Natasha), Henry Fonda (Pierre) and Mel Ferrer (Andrei). Audrey Hepburn was nominated for a BAFTA Laurels for best British actress and for a Golden Globe Honour for all-time actress in a drama production.

- The critically acclaimed, iv-part and 431-minutes long Soviet State of war and Peace, by director Sergei Bondarchuk, was released in 1966 and 1967. Information technology starred Lyudmila Savelyeva (every bit Natasha Rostova) and Vyacheslav Tikhonov (as Andrei Bolkonsky). Bondarchuk himself played the character of Pierre Bezukhov. It involved thousands of extras and took six years to finish the shooting, as a event of which the actors historic period changed dramatically from scene to scene. It won an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film for its authenticity and massive scale.[ citation needed ] Bondarchuk'due south film is considered to be the best screen version of the novel. It attracted some controversy due to the number of horses killed during the making of the battle sequences and screenings were actively boycotted in several Us cities by the ASPCA.[39]

Television [edit]

- State of war and Peace (1972): The BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) made a television serial based on the novel, circulate in 1972–73. Anthony Hopkins played the atomic number 82 role of Pierre. Other lead characters were played by Rupert Davies, Faith Brook, Morag Hood, Alan Dobie, Angela Downwards and Sylvester Morand. This version faithfully included many of Tolstoy'southward minor characters, including Platon Karataev (Harry Locke).[xl] [41]

- La guerre et la paix (2000): French Television receiver production of Prokofiev's opera War and Peace, directed past François Roussillon. Robert Brubaker played the lead role of Pierre.[42]

- War and Peace (2007): produced past the Italian Lux Vide, a TV mini-series in Russian & English co-produced in Russia, France, Germany, Poland and Italy. Directed past Robert Dornhelm, with screenplay written by Lorenzo Favella, Enrico Medioli and Gavin Scott. It features an international cast with Alexander Beyer playing the atomic number 82 role of Pierre assisted by Malcolm McDowell, Clémence Poésy, Alessio Boni, Pilar Abella, J. Kimo Arbas, Ken Duken, Juozapas Bagdonas and Toni Bertorelli.[43]

- On 8 December 2015, Russian state television channel Russian federation-K began a four-day broadcast of a reading of the novel, 1 volume per day, involving one,300 readers in over 30 cities.[44]

- War & Peace (2016): The BBC aired a vi-part adaptation of the novel scripted by Andrew Davies on BBC I in 2016.[45] [46]

Music [edit]

- English progressive rock ring Yeah'south song "The Gates of Delirium" from their 1974 album Relayer was inspired by War and Peace.

Opera [edit]

- Initiated past a proposal of the High german director Erwin Piscator in 1938, the Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev composed his opera War and Peace (Op. 91, libretto past Mira Mendelson) based on this ballsy novel during the 1940s. The complete musical work premièred in Leningrad in 1955. It was the outset opera to be given a public performance at the Sydney Opera House (1973).[47]

Theatre [edit]

- The first successful stage adaptations of State of war and Peace were produced by Alfred Neumann and Erwin Piscator (1942, revised 1955, published by Macgibbon & Kee in London 1963, and staged in 16 countries since) and R. Lucas (1943).

- A stage adaptation by Helen Edmundson, starting time produced in 1996 at the Regal National Theatre with Richard Promise as Pierre and Anne-Marie Duff as Natasha, was published that year by Nick Hern Books, London. Edmundson added to and amended the play[48] for a 2008 production as two 3-60 minutes parts by Shared Feel, again directed by Nancy Meckler and Polly Teale.[49] This was first put on at the Nottingham Playhouse, and then toured in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland to Liverpool, Darlington, Bath, Warwick, Oxford, Truro, London (the Hampstead Theatre) and Cheltenham.

- A musical adaptation by OBIE Award-winner Dave Malloy, called Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 premiered at the Ars Nova theater in Manhattan on October i, 2012. The show is described every bit an electropop opera, and is based on Book viii of War and Peace, focusing on Natasha's matter with Anatole.[50] The show opened on Broadway in the fall of 2016, starring Josh Groban as Pierre and Denée Benton as Natasha. It received twelve Tony Honor nominations including Best Musical, Best Actor, All-time Extra, All-time Original Score, and All-time Volume of a Musical.

Radio [edit]

- The BBC Home Service broadcast an viii-part adaptation past Walter Peacock from 17 January to 7 Feb 1943 with two episodes on each Sun. All only the terminal instalment, which ran for i and a one-half hours, were one 60 minutes long. Leslie Banks played Pierre while Celia Johnson was Natasha.

- In Dec 1970, Pacifica Radio station WBAI broadcast a reading of the entire novel (the 1968 Dunnigan translation) read by over 140 celebrities and ordinary people.[51]

- A dramatised full-cast adaptation in 20 parts, edited by Michael Bakewell, was broadcast by the BBC between 30 December 1969 and 12 May 1970, with a bandage including David Cadet, Kate Binchy and Martin Jarvis.

- A dramatised total-cast adaptation in ten parts was written past Marcy Kahan and Mike Walker in 1997 for BBC Radio iv. The production won the 1998 Talkie award for Best Drama and was around ix.5 hours in length. It was directed by Janet Whitaker and featured Simon Russell Beale, Gerard Potato, Richard Johnson, and others.[52]

- On New year's Day 2015, BBC Radio four[53] broadcast a dramatisation over 10 hours. The dramatisation, by playwright Timberlake Wertenbaker, was directed past Celia de Wolff and starred Paterson Joseph and John Injure. It was accompanied by a Tweetalong: alive tweets throughout the day that offered a playful companion to the book and included plot summaries and entertaining commentary. The Twitter feed also shared maps, family trees and battle plans.[54]

See besides [edit]

- Leo Tolstoy bibliography

- Listing of historical novels

- Volkonsky House

- War and Peas

- Mir

References [edit]

- ^ Moser, Charles. 1992. Encyclopedia of Russian Literature. Cambridge University Press, pp. 298–300.

- ^ Thirlwell, Adam "A masterpiece in miniature". The Guardian (London, United kingdom) Oct 8, 2005

- ^ Briggs, Anthony. 2005. "Introduction" to War and Peace. Penguin Classics.

- ^ a b Pevear, Richard (2008). "Introduction". State of war and Peace . Trans. Pevear; Volokhonsky, Larissa. New York: Vintage Books. pp. Eight–IX. ISBN978-i-4000-7998-8.

- ^ a b Knowles, A. V. Leo Tolstoy, Routledge 1997.

- ^ "Introduction?". War and Peace. Wordsworth Editions. 1993. ISBN978-1-85326-062-nine . Retrieved 2009-03-24 .

- ^ Hare, Richard (1956). "Tolstoy's Motives for Writing "State of war and Peace"". The Russian Review. 15 (2): 110–121. doi:10.2307/126046. ISSN 0036-0341. JSTOR 126046.

- ^ Thompson, Caleb (2009). "Quietism from the Side of Happiness: Tolstoy, Schopenhauer, War and Peace". Common Knowledge. fifteen (3): 395–411. doi:10.1215/0961754X-2009-020.

- ^ a b c Kathryn B. Feuer; Robin Feuer Miller; Donna Tussing Orwin (2008). Tolstoy and the Genesis of War and Peace. Cornell University Press. ISBN978-0-8014-7447-7 . Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ^ Emerson, Caryl (1985). "The Tolstoy Connectedness in Bakhtin". PMLA. 100 (1): 68–80 (68–71). doi:10.2307/462201. JSTOR 462201.

- ^ Hudspith, Sarah. "Ten Things You Need to Know Virtually War And Peace". BBC Radio 4 . Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Pearson and Volokhonsky, op. cit.

- ^ Troyat, Henri. Tolstoy, a biography. Doubleday, 1967.

- ^ a b c d Figes, Orlando (Nov 22, 2007). "Tolstoy's Existent Hero". New York Review of Books. 54 (eighteen): 53–56. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ Flaitz, Jeffra (1988). The ideology of English: French perceptions of English equally a world language. Walter de Gruyter. p. 3. ISBN978-3-110-11549-nine . Retrieved 2010-11-22 .

- ^ a b Inna, Gorbatov (2006). Catherine the Great and the French philosophers of the Enlightenment: Montesquieu, Voltaire, Rousseau, Diderot and Grim. Academica Press. p. 14. ISBN978-1-933-14603-4 . Retrieved iii December 2010.

- ^ a b c Tolstoy, Leo (1949). State of war and Peace. Garden Metropolis: International Collectors Library.

- ^ Leo Tolstoy, State of war and Peace. p. 317

- ^ Tolstoy p. 340

- ^ Sukhikh, Igor (2007). "The History of XIX Russian literature". Zvezda . Retrieved 2012-03-01 .

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Opulskaya, Fifty.D. State of war and Peace: the Epic. L.N. Tolstoy. Works in 12 volumes. State of war and Peace. Commentaries. Vol. 7. Moscow, Khudozhesstvennaya Literatura. 1974. pp. 363–89

- ^ Zaitsev, V., Pearls and Adamants of Russian Journalism. Russkoye Slovo, 1865, #2.

- ^ Kuzminskaya, T.A., My Life at home and at Yasnaya Polyana. Tula, 1958, 343

- ^ Gusev, N.I. Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy. Materials for Biography, 1855–1869. Moscow, 1967. pp. 856–57.

- ^ The Literature Archive, vol. 6, Academy of Science of the USSR, 1961, p. 81

- ^ Literary Archive, p. 94

- ^ Literary Archive, p. 104.

- ^ The Beginnings (Nachala), 1922. #2, p. 219

- ^ Dostoyevsky, F.M., Letters, Vol. III, 1934, p. 206.

- ^ Gusev, p. 858

- ^ Gusev, pp. 863–74

- ^ The Complete I.S. Turgenev, vol. XV, Moscow; Leningrad, 1968, 187–88

- ^ Motylyova, T. Of the worldwide significance of Tolstoy. Moscow. Sovetsky pisatel Publishers, 1957, p. 520.

- ^ Literaturnoye Nasledstsvo , vol. 75, volume one, p. 61

- ^ Literaturnoye Nasledstsvo , vol. 75, volume 1, p. 173

- ^ "Introduction to War and Peace" by Richard Pevear in Pevear, Richard and Larissa Volokhonsky, War and Peace, 2008, Vintage Classics.

- ^ Greenwood, Edward Baker (1980). "What is War and Peace?". Tolstoy: The Comprehensive Vision. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 83. ISBN0-416-74130-4.

- ^ Pavlovskis-Petit, Zoja. Entry: Lev Tolstoi, War and Peace. Classe, Olive (ed.). Encyclopedia of Literary Translation into English, 2000. London, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, pp. 1404–05.

- ^ Curtis, Charlotte (2007). "State of war-and-Peace". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Baseline & All Movie Guide. Archived from the original on 2007-ten-thirteen. Retrieved 2014-04-20 .

- ^ State of war and Peace. BBC Two (ended 1973). TV.com. Retrieved on 2012-01-29.

- ^ War & Peace (TV mini-series 1972–74) at IMDb

- ^ La guerre et la paix (TV 2000) at IMDb

- ^ War and Peace (TV mini-series 2007) at IMDb

- ^ Overflowing, Alison (8 December 2015). "Four-day marathon public reading of War and Peace begins in Russian federation". The Guardian.

- ^ Danny Cohen (2013-02-eighteen). "BBC 1 announces adaptation of War and Peace past Andrew Davies". BBC. Retrieved 2014-04-20 .

- ^ "War and Peace Filming in Lithuania".

- ^ History – highlights. Sydney Opera House. Retrieved on 2012-01-29.

- ^ Cavendish, Dominic (February xi, 2008). "War and Peace: A triumphant Tolstoy". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008.

- ^ "War and Peace". Archived from the original on 2008-12-20. Retrieved 2008-12-xx . . Sharedexperience.org.uk

- ^ Vincentelli, Elisabeth (October 17, 2012). "Over the Moon for Comet". The NY Mail. New York.

- ^ "The War and Peace Broadcast: 35th Anniversary". Archived from the original on 2006-02-09. Retrieved 2006-02-09 . . Pacificaradioarchives.org

- ^ "Marcy Kahan Radio Plays". War and Peace (Radio Dramatization) . Retrieved 2010-01-twenty .

- ^ "War and Peace - BBC Radio 4". BBC.

- ^ Rhian Roberts (17 Dec 2014). "Is your New Year resolution finally to read War & Peace?". BBC Blogs.

External links [edit]

- English Text

- English translation with commentary by the Maudes at the Cyberspace Archive

- English translation at Gutenberg

- War and Peace, from Marxists.org

- War and Peace, from RevoltLib.com

- State of war and Peace' , from TheAnarchistLibrary.org

- War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1863-1869). Illustrated past A. Apsit (1911-1912)

- Searchable version of the gutenberg text in multiple formats SiSU

- War and Peace at the Internet Book Listing

- A searchable online version of Aylmer Maude's English translation of War and Peace

- English Audio

-

War and Peace public domain audiobook at LibriVox

War and Peace public domain audiobook at LibriVox

-

- Commentaries

- Homage to State of war and Peace Searchable map, compiled past Nicholas Jenkins, of places named in Tolstoy's novel (2008).

- Birth, death, assurance and battles past Orlando Figes. This is an edited version of an essay institute in the Penguin Classics new translation of War and Peace (2005).

- Summaries

- Chapter Summaries for War and Peace

- SparkNotes Study Guide for War and Peace

- In Electric current Events

- Radio documentary about 1970 marathon reading of State of war and Peace on WBAI, from Republic At present! program, December 6, 2005

- Russian Text Online

- Full text of State of war and Peace in mod Russian orthography

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_and_Peace

إرسال تعليق for "Chapter 5 War Peace and War Again"